862 M A T E R I A L S E V A L U A T I O N • J U L Y 2 0 2 0 deployment period, the technology gets used to its full extent. Along this line, Industry 4.0 can be considered the deploy- ment period of digital technologies, and the period between 1970 and 2000 was the installation period. One of the findings of this type of analysis is that most technology imple- mented in the deployment period already existed before that period. The authors believe the same to be true for Industry 4.0, and especially for NDT 4.0, given the record of innovation in NDT (Wassink 2012), where technologies often get implemented decades after other sectors use them. In the literature on Industry 4.0, several key attributes are listed. These include integration of value and supply chains, interconnectedness of processes, decentralized decision making, and customization of product offerings. Many of these have a relationship with the supply chain. Therefore, the authors will start the discussion of the case studies with a look at the inspection and maintenance supply chain. Introduction to Case Studies In the next section, a number of cases will be discussed that will show how features of NDT 4.0 are being realized in new products. The first case study will discuss heat exchanger tube testing and will highlight developments in automated inter- pretation software using AI. It will also touch on issues related to cloud storage of data. The second case study will discuss the inspection of storage tanks and will highlight develop- ments in software for maintaining a digital twin. The final case study will discuss the inspection of pressure vessels and will highlight the development of software for adaptive inspection of complex geometries. Case Study 1: Heat Exchanger Tube Testing Tube testing is performed during the in-service life cycle stage of heat exchangers and is typically delivered by a specialist service provider or internal department to the owner/operator of the equipment. Over the last decade, equipment for tube testing has become more widely available, and more service providers have started to offer the service. This has led to an increased concern about the quality of testing and an increased demand for stan- dardization, evident from projects in industry bodies such as the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI), American Petroleum Institute (API), and HOIS (a joint industry project with more than 40 participating partners). The actual test needs to be performed after the equipment has been taken out of service. Getting the equipment back in service on time is important. The work involves testing hundreds of individual tubes, and testing a single heat exchanger may take many hours. In addition, the results of a heat exchanger test may give important clues about the cause of failure and may prompt additional maintenance activities before the heat exchanger is put back into service. In this context of high productivity, NDT 4.0 technologies and concepts can play an important role in improving efficiency, reliability, and the confidence level in the overall heat exchanger inspection process. Smart sensors, accessories, and software can support service companies and asset owners by: l providing better traceability of the data throughout the inspection process l assisting the operator in crucial steps that could affect the data integrity l improving the analyst efficiency in data interpretation, including the automatic detection and classification of indications l providing realistic 3D heat exchanger representations to facilitate interpretation (Figure 1) l promoting the sharing of data, analysis, and reports based on secure cloud services Current equipment enables full traceability of instruments, probes, configurations, and metadata related to the test condi- tion, including building a testing history of a specific heat exchanger. This again enables the smart use of data for auditing and risk-based inspection (RBI) to maximize the in-service period of the asset. In addition, projects are ongoing for creating a tool to automate the interpretation of heat exchanger results. At first, this will be implemented through assisted analysis to the techni- cian. A huge effort is currently made to integrate an AI processing technique to perform data quality validation during acquisition as well as automatic data screening. The conventional eddy current bobbin probe inspection is already well accommodated by those automated processes, and the automation of other tube inspection techniques (such as remote field testing, near field testing, and eddy current array) is under active development. The goal is to drastically reduce the number of tubes to review so that the analyst can concentrate on the most challenging tubes. On top of decreasing the influence of the human factor in analysis, this will create feedback that helps train the technician. Currently, the AI classifiers, created using open source tools, have been running in beta trials with some service providers. The performance of these algorithms shows increased performance over previous rule-based algorithms for example, bringing the position error of tube features from 9.4% down to 2.3%. Figure 1 shows a 3D representation of a heat exchanger with defects graphically marked and the result of feature detection software. Although every test starts with a good sensor that provides high-quality data, digitization may help in several other ways. The testing results can be made available online, in the cloud, or connected in real time. Some service companies are already doing this by using commercial cloud-based solutions such as OneDrive, Google Drive, or Dropbox, but those solutions are not optimized for NDE. An optimized solution would offer different types of access depending on the ownership relation- ship with the asset and the data. Such cloud services will be useful for the service companies to perform data analysis with remote Level III experts to provide immediate feedback to the acquisition crew for any area of concern that may need to be rescanned. The cloud also plays a role in sending automated messages to the company level when the equipment starts ME TECHNICAL PAPER w digital ndt solutions

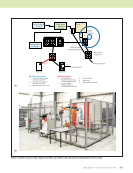

J U L Y 2 0 2 0 • M A T E R I A L S E V A L U A T I O N 863 running outside the boundaries set at instrument validation, in order to share instrument configuration, historical data, and reports. For the owner/operator, it could mean receiving real- time feedback of testing results, monitoring inspection progres- sion, and consulting realistic 3D tube sheets and bundle maps, which enable spotting of patterns in the occurrence of defects and helps determine the underlying problems to degradation. This could definitively help to smooth turn-around planning. The processing of data using cloud processing has been achieved and trialed as well, but issues concerning data ownership and data security have, so far, limited the applica- tion of cloud storage and processing as a commercial model. Case Study 2: Storage Tank Testing Storage tanks may operate for many years without interrup- tion. Maintenance windows are small, and, depending on the stored product, the tank may be emptied for inspection and repair only once every 20 years. The inspection of a storage tank tends to use a range of technologies for its components such as the floor, wall, roof, and ancillaries. This may involve one service provider, or several, and results may be delivered directly to the owner, or to an intermediary such as a mainte- nance contractor. As supply relationships are very diverse, there is an obligation to use open data formats if digital inte- gration is to be achieved. One of the most common is simple comma-separated values (CSV) files. With large amounts of data available, oil companies have started to harness the idea of digital twins in order to gain a better holistic insight into the behavior and life expectancy of their equipment. This can begin by first creating a virtual representation of the structure in computer-aided design (CAD) software. Data gathered from recent inspections can then be used to adjust the digital twin to create a current-case model of the asset. This could be done by deforming the 3D model itself or with a color-coded textured overlay of recorded maps from corrosion-mapping tools. This would result in a benchmark representation of the asset. Further information, such as historic inspections and previous repairs, could be added to the digital twin to complete its virtual representation. This baseline model is considered the “initial- ization” stage of the digital twin and is represented by the first stage in the life of a digital twin, as illustrated in Figure 2. Digital twin baseline Physical asset Key frame audit ● Perform inspection Digital twin ● 3D point cloud ● CAD drawing Inspection ● Assess the present condition Historical data ● Archived inspection reports ● Historic inspection data Update digital twin ● Establish new baseline Schedule maintenance Monitoring Update digital twin Decommission asset Fit for purpose? Yes No Out of service In service (1–20 year period) Digital twin creation (initialization) Figure 2. Simple illustration of the creation of a digital twin and its upkeep throughout the life of an asset. Feature tags Legend with feature tags Scan results of tube Complex plane eddy current signals Figure 1. Nondestructive testing of a heat exchanger: (a) 3D representation after testing showing defects and flawed tubes (b) results of feature detection software. (a) (b)

ASNT grants non-exclusive, non-transferable license of this material to . All rights reserved. © ASNT 2026. To report unauthorized use, contact: customersupport@asnt.org