864 M A T E R I A L S E V A L U A T I O N • J U L Y 2 0 2 0 Magnetic flux leakage (MFL) scanners have been collecting and digitizing information relating to the condition of tank floors for 20 years. Early adopters of MFL scanners from as early as 1999 can use their data as historic records to feed into the creation (or updating) of the digital twin (Figure 3). This data provides some history of the asset’s condition and can be used in conjunction with other inspection modalities or subsequent MFL inspections to identify any common trends, which is ideal for scheduling the next out-of-service interval. This then feeds into the third stage in Figure 2, which represents an out- of-service interval where a detailed internal inspection can be performed. One component of this stage is that the detailed inspection can be used to fully update the baseline condition of the digital twin because during the in-service stage, there will be a limited amount of information available to update. Data is the center of Industry 4.0, and although semi- or auto- mated procedures can provide a huge benefit with large-scale data sets, even simple visual inspections with checklists can be used to bolster the information to the digital twin, continually improving its representation. This is considered a “keyframe” audit, which can be used to reset the baseline of the existing model to be used for the next in-service cycle. It is also important to note that advancements in inspec- tion systems can be considerable between out-of-service inter- vals. This can add complications as the data may no longer have the same format, and newer inspection systems may present the same defect differently. However, the increased quality and new information available from contemporary inspection systems (for example, top-side/bottom-side auto- mated discontinuity recognition with improved sensors [Pearson and Boat 2012]) can also enhance the keyframe audit and add further value when used to readjust the baseline periodically. In current digital twinning software for the tank bottom, through signal processing algorithms, discontinuities can now be automatically segmented and fed into RBI analysis tools to predict the time until the next maintenance activity is needed and the overall remaining tank life. Development work includes features that will enable automatic fitting of the scan data on the digital image of the tank. From this data, repair plans for the tank floor can be generated to enable faster maintenance activities. Over time, through subsequent scanning or periodic monitoring, sensor information can be used to update the representation of the tank floor and bring it up to its present condition. As gaining access to the tank floor when the tank is in service is challenging, updating the digital twin during the monitoring stage can be limited. To advance the in-service aspect of inspection, developments are ongoing for incorpo- rating equipment into robots that can inspect the storage tank while filled. Tanks that contain product may have substantial contaminations on the tank bottom, which need to be tested through. A pulsed eddy current system has been tested in this environment and phased array ultrasonic testing (PAUT) will be soon evaluated. The complementarity of these two tech- niques should allow, in the coming months, a reliable way of monitoring tank floors between major shutdowns. Alternatively (or in tandem), fixed Internet of Things (IoT) sensors permanently placed on the tank floor may be used to perform remote and perhaps wireless transmissions of data. At present, this remains a challenge, but if made avail- able, such sensors could monitor areas of localized corrosion discovered during the tank’s last MFL inspection. This brings us to one important note for NDT 4.0, which is the security of the readily available and popular IoT range of devices. One must consider that these devices are aimed to be always connected and potentially vulnerable to attack. For example, smart sensor spoofing could be one area where security needs to be considered. In spoofing, an attacker may mimic the smart sensor and send fraudulent readings to the digital twin ME TECHNICAL PAPER w digital ndt solutions Figure 3. Tank floor inspection: (a) digital twinning software (b) screenshot of software showing a comparison of new (top) and old (bottom) data from the same floor plate. (a) (b)

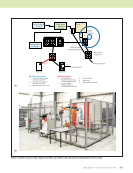

J U L Y 2 0 2 0 • M A T E R I A L S E V A L U A T I O N 865 monitoring station, resulting in false alarms and disrupting productivity. Suitable security for these connected devices needs to be addressed, particularly as condition monitoring with smart sensors becomes more common. Monitoring the accessible surfaces of the storage tank can be carried out through nonintrusive inspection. Components of the digital twin, such as the roof and tank shell, can be updated more frequently. Among standard manual techniques, there are many benefits to utilizing robotics for example, a robotic crawler can scale the tank wall to record a thickness profile without the need for expensive scaffolding (Figure 4). Several vertical profiles can be taken around the tank, with their frequency usually depending on the tank’s diameter. A remote crawler offers enhanced safety through remote inspection and culminates in a graphical digital record. When using a dry- coupled ultrasonic wheel probe (which adds portability), the thickness profile helps to identify any ring corrosion generated at a maintained product level. Such corrosion can be correlated with the number of scans taken around the periphery of the tank, but also note that this will provide a greater probability of detection than traditional manual thickness measurements on a sparse grid separation. The data itself serves as a record and input to the asset’s digital twin. Capturing the inspection results of the various technolo- gies in a digital twin of the tank will, in the future, also enable more advanced forecasting of degradation through prediction modeling in order to determine future capabilities of the storage tank. Case Study 3: Nonintrusive Vessel Testing In addition to the technologies discussed in the section on storage tanks, a virtual representation needs to mimic the condition of an asset to provide a picture of its current state or enough information to perform risk analysis and schedule maintenance. Having as much “good” data as possible about the condition of the asset is paramount in order to facilitate decision making. For example, fit-for-purpose decisions would greatly benefit from knowing the most accurate condition of a vessel wall through mapping, as similarly described for tank shell walls. One of the most discussed trends in the oil industry is the requirement to no longer enter confined spaces. Where until now vessels were often inspected visually by a person entering them, several oil companies have expressed that they will no longer allow this. This means two possibilities: inspect from the exterior or utilize a remote robotic system on the inside. Automated NDT is essential for many industries where main- taining and evaluating the safety of components is crucial. Applying automation can increase not only safety but the overall longevity of an asset with an increase in measurement and positional accuracy, as well as cost benefits through effi- ciency. One key component of Industry 4.0 is the reduction in human errors. One example of applying automation to improve produc- tivity is automated ultrasonic inspection and its impact on inspection quality and consistency on large assets such as pipelines, vessels, and storage tanks (Figure 5). The inspection Figure 4. Nonintrusive tank inspection: (a) remote crawler utilizing dry-coupled UT (b) MFL floor scanning for out-of-service tank. (a) (b)

ASNT grants non-exclusive, non-transferable license of this material to . All rights reserved. © ASNT 2026. To report unauthorized use, contact: customersupport@asnt.org