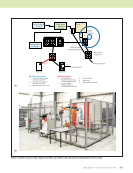

876 M A T E R I A L S E V A L U A T I O N • J U L Y 2 0 2 0 to this early interface as simply “red light/green light.” However, during transition, when a call was made by the algo- rithm, the question of “Why was the call made?” would imme- diately follow. Enhancements were made to the software to provide more specific feedback on called indications and highlight when data was not adequate for making indication calls. A couple examples of hole indications being too weak or cut off to make proper calls are shown in Figure 3. As well, certain severe structure-plus-fastener conditions were found to produce false calls on rare occasions. To manage these false calls by the algorithm, the results and raw data required a secondary review by inspectors. Inspectors were trained on what to look for in the B-scan to manage this limitation with the algorithm. Although this technique was the first AI/neural network–based approach used to inspect a portion of the USAF C-130 fleet, this case study is actually a very good example of IA in practice. Lessons Learned on Improving the Human-Machine Interface Ultrasonic testing is one of the most effective methods to detect critical defect types and ensure the reliability of aero- space polymer matrix composite structures. Most inspection applications of composites are based on pulse-echo ultrasonic testing and manual C-scan data interpretation. Using ampli- tude and TOF C-scan data, delaminations, disbonds, porosity, and foreign materials can be detected and located in depth. However, the ultrasonic inspection of large composite structures requires a significant work force and production time. To address this inspection burden, ADA software tools were developed and implemented (Aldrin et al. 2016a). The ADA minimizes the inspector’s burden on performing mundane tasks and allocates their time to analyze data of primary interest. When the algorithm either detects a feature in the data that is unexpected or that is found to be represen- tative of a defect, then the indication is flagged for further analysis by the inspector. A software interface for the ADA toolkit is shown in Figure 4. The main view provides a summary of the found indications in the analyzed data, a visual presentation of an indication map, and quantitative metrics assisting the operator in understanding why each call was made. An example of ADA processing results is reported in the interface display shown in Figure 4. Options are provided to enter feedback into the “review” column to indicate if certain calls are incorrect. This example specimen contains artificial defects that have been added at varying locations and ply depth, including above and below the adhesive layer. Indica- tions are listed in the spreadsheet display in the upper left, and corresponding numbers are presented identifying the indica- tions in the C-scan image display on the right. For these ADA evaluations of the two different scan orientations, the three triangular inserts in the bond region were all correctly called. The left-most triangle is in front of the bond and the right two triangles are behind the bond. Indications for the six inserted ME TECHNICAL PAPER w ia and human-machine interfaces Bond region indications “Sticky note” indication Figure 4. Example ADA toolkit interface with results for a test panel with embedded artificial defects, scanned from tool side, with time of flight C-scan view (adapted from Aldrin et al. 2016a).

J U L Y 2 0 2 0 • M A T E R I A L S E V A L U A T I O N 877 materials at the radii are also observed in the TOF map in Figure 4. As well, there are options to add uncalled indications as missed calls into the ADA report with comments. Lastly, features are also provided to support verification of calibration scans, detecting the file and matching the indication calls with expected calibration results. During this development program, feedback from the team and end users was critical in delivering the necessary capability. Ensuring NDT 4.0 Reliability A helpful model to represent the reliability of an inspection system has been introduced by Müller and others (Müller et al. 2000, 2014). Total reliability of an NDT system is defined by the intrinsic capability of the system, providing an upper bound for the technique under ideal conditions, with contri- butions from application parameters, the effect of human factors, and organization context that can degrade the performance. While NDT 4.0 systems are expected to enhance POD performance through improved human factors (supporting ease of use) and repeatability in making complex calls with varying application parameters, NDT 4.0 capability must be evaluated. NDT techniques, whether incorporating AI algorithms, manual inspector data review, or a mixed IA-based approach, require validation through a POD evaluation. Comprehensive POD evaluation procedures (US DOD 2009 ASTM 2015) have been developed to validate the reliability of NDT techniques, regardless of how the indication call is made. In prior work, a POD study was conducted to evaluate the capability of an ADA algorithm to detect cracks around holes in vertical riser aircraft structures (Aldrin et al. 2001). In the study, an ADA approach incorporating neural networks was compared with manual data review by inspectors. Results demonstrated that the automated neural network approach was significantly improved in both detectability, false call rate, and inspection time relative to manual data interpretation (Aldrin et al. 2001). Other recent studies have also addressed the role of POD evaluation when human factors are involved (Bato et al. 2017). The greatest challenge with validation of NDT algorithms is ensuring that the algorithm is not overtrained but can handle the variability of practical NDT measurements outside of the laboratory. Testing algorithms with independent samples with respect to training data is critical. Model-assisted approaches for training (Fuchs et al. 2019) and validation (Aldrin et al. 2016b) will help provide a diversity of condi- tions beyond what is practical and cost-effective with experi- mental data only. Because of these challenges, properly validating NDT techniques using IA is expected to be far easier than a purely AI-based technique. For the example of validating self-driving car technology, simply augmenting the driver experience with collaborative safety systems is much more straightforward to validate than fully validating an AI only–based self-driving car technology. Recent accidents during the testing of self-driving cars indicate the care that is needed to properly and safely validate such fully automated systems when lives are at stake. Lastly, at this early stage in the application of AI and IA, there are currently no certification requirements for people who design and/or train such algorithms. However, as the field matures, such best practices should be shared throughout the community and included in accredited training programs. Over time, the potential value of imple- menting certification programs should be considered, possibly under the umbrella of NDT engineering. Conclusions and Recommendations While an increasing use of automation and algorithms in NDT is expected over time, NDT inspectors will play a critical role in ensuring NDT 4.0 reliability. As a counterpoint to AI, IA was presented as an effective use of information technology to enhance human intelligence. Based on prior experience, this paper introduces a series of best practices for IA in NDT, highlighting how the operator should ideally interface with NDT data and algorithms. Algorithms clearly have a great potential to help alleviate the burden of big data in NDT however, it is important that operators are involved in both secondary indication review and the detection of rare event indications not addressed well by typical algorithms. In addition, IA provides more flexibility with the application of AI. When applications are not a perfect fit for existing AI algo- rithms, a human user can adapt and leverage the benefits of AI appropriately. Future work should continue to address the validation of NDT techniques that leverage both humans and algorithms for data review and investigate appropriate process controls and software design to ensure optimal performance. Currently, AI algorithms are being developed primarily by engineers to perform very specific tasks, but there may come a time soon when AI tools are more adaptive and offer collabo- rative training. It is important for adaptive AI algorithms to maintain a core competency while also providing flexibility and learning capability. Care must be taken to avoid having an algorithm “evolve” to a poorer level of practice, due to bad data, inadequate guidance, or deliberate sabotage. Like computer viruses today, proper design practices and FMEA are needed to ensure such algorithms are robust to varying conditions. It is important to design these systems to periodi- cally do self-checks on standard data sets, similar to how inspectors must verify NDT systems/transducers using stan- dardization procedures or having inspectors perform NDT examinations periodically. Lastly, NDT 4.0–connected initiatives such as digital threads and digital twins are examples of how material systems can be better managed in the future (Kobryn et al. 2017 Lindgren 2017). The digital thread provides a means to track all digital information regarding the manufacturing and sustain- ment of a component and system, including the material state and any variance from original design parameters. The digital

ASNT grants non-exclusive, non-transferable license of this material to . All rights reserved. © ASNT 2026. To report unauthorized use, contact: customersupport@asnt.org