874 M A T E R I A L S E V A L U A T I O N • J U L Y 2 0 2 0 standards (such as DICONDE and HDF5) and incorpo- rating flexible software architectures, will greatly accelerate the evolution of these systems (Meier et al. 2017 Vrana et al. 2018). l Reliability must be demonstrated for NDT 4.0 systems. The capability of inspection procedures incorporating NDT 4.0 systems that depend on the performance of both algorithms and the NDT inspector must be evaluated jointly. Probability of detection (POD) evaluation procedures, such as MIL-HDBK-1823A (US DOD 2009), are designed to validate the reliability of NDT techniques, regardless of how the indication call is made. l Software and algorithms can also support NDT reliability as process controls. Simply demonstrating POD capability does not ensure reliability of the technique (Rummel 2010). FMEA should be performed for all NDT techniques incorpo- rating automation to understand the potential sources for poor reliability (Bertović 2016a). In practice, NDT reliability depends on a reproduceable calibration procedure and a repeatable inspection process (Rummel 2010). Process controls and algorithms can thus be used to ensure all cali- bration indications are verified and to track key metrics that show the NDT process is repeatable over time and under control. As an example, recent work on model-based inverse algorithms with eddy current inspections has shown the potential to reduce error due to variability in probes through calibration process controls (Aldrin et al. 2017). NDT 4.0 systems are also expected to improve the safety of inspections in dangerous environments. By collecting environmental conditions (using environmental sensors and/or weather monitoring) and test system state data from the site, one can ensure the reliability of the inspection task and reduce the level of risk for all involved. l Build trust over time and consider the cost-benefit for future algorithms and user interface enhancements. Managing costs and mitigating risk drive most decisions for NDT today. For organizations that depend on NDT, there are likely certain applications that will provide the greatest payoff in terms of cost and quality for their customers, transitioning from conventional NDT ME TECHNICAL PAPER w ia and human-machine interfaces Area being inspected Inboard Location of web Fasteners Exterior Interior Ultrasonic signal sent in at angle to propagate down vertical leg to fastener holes Transducer Wing skin Vertical leg Potential crack locations Figure 2. Inspection of beam cap holes in C-130 aircraft: (a) photo of area being inspected (looking forward) and (b) diagram of inspection problem (from Lindgren et al. 2005). (a) (b)

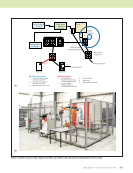

J U L Y 2 0 2 0 • M A T E R I A L S E V A L U A T I O N 875 to NDT 4.0. The transition of algorithms should initially be a phased approach, to both validate the algorithm’s performance and build an understanding of where algo- rithms are reliable and where limitations exist. By tracking called indications over time, it becomes feasible to refine algorithms as necessary. Building that experience internally and achieving an initial payoff will lead to a broader transi- tion of these best practices across an organization and greater shareholder value. Organizational change manage- ment must ease this transition through the proper training of inspectors and also management of expectations. Applications Several case studies are presented in the following sections that highlight these best practices of leveraging algorithms in NDT applications and addressing human-machine interfaces. These early examples can be considered in the context of a minimal viable product, providing a product with just enough features to satisfy early requirements and provide feedback for future product development. These examples provide key insight on both the promise for NDT 4.0 applications as well as opportunities for future improvement. Early Example Where AI Vision Becomes IA in Practice Following the success of the C-141 weep hole inspection program (Aldrin et al. 2001), the development of automated data analysis algorithms was investigated for the inspection of beam cap holes in US Air Force (USAF) C-130 aircraft (Figure 2a) (Lindgren et al. 2005). Here, the fastener sites of interest were in locations of limited accessibility from the external surface and contain fasteners with sealant (Figure 2b). Due to limitations with the NDT capability at the time, there was a need to develop improved ultrasonic techniques to detect fatigue cracks at these locations. A key challenge was the ability to discern multiple signals originating from a possible crack and a geometric feature in a part that was either closely spaced or superimposed in time. The C-130 beam cap holes provided a special challenge given the skewed riser, installed fasteners, and limited transducer accessibility of the B-scan inspection (Figure 2b). This inspection problem frequently produced reflections from the fastener hole (referred to as reradiated insert signals) occurring at similar times of flight (TOF) as near and far crack signals. To address this challenge, a novel feature extraction methodology was developed to detect the relative shift of signals in time for adjacent transducer loca- tions due to differing echo dynamics from cracks and part geometries (Aldrin et al. 2006). This technique was the first ultrasonic NDT method using assisted data analysis methods, validated through a POD study, to inspect for fatigue cracks on USAF structures (Lindgren et al. 2005). A view of the operator’s user interface, dating back to 16 years now, is presented in Figure 3. The original vision for the approach was to have the automated data analysis (ADA) algorithms make all of the indication calls. The team referred –1 = Signal too weak from hole increase gain and rerun –4 = Hole signal cut off expand scan range and rerun RIS = Reradiated insert signals (due to tight fastener fit) Figure 3. Graphical user interface for automated data analysis (ADA) software incorporating neural network classifiers.

ASNT grants non-exclusive, non-transferable license of this material to . All rights reserved. © ASNT 2026. To report unauthorized use, contact: customersupport@asnt.org