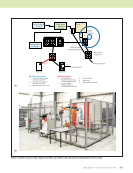

870 M A T E R I A L S E V A L U A T I O N • J U L Y 2 0 2 0 NDT 4.0 software and hardware. Care must be taken with the implementation of automation to ensure that operators have the necessary awareness and control as needed. In addition, as a counterpoint to recent advances in AI algorithms, intelli- gence augmentation (IA) is introduced as the effective use of information technology to enhance human intelligence. From this perspective, the inspector is an integrated part of NDT 4.0 systems and performs necessary tasks in collaboration with automated NDT systems and data analysis algorithms. This paper will present a series of best practices for the interface between NDT hardware, software, and algorithms and human inspectors and engineers to ensure NDT 4.0 reliability. Algorithms and AI in NDT NDT algorithms that perform indication detection and char- acterization can be organized into three classes: (1) algorithms based on NDT expert knowledge and procedures (heuristic algorithms) (2) model-based inversion and (3) algorithms incorporating statistical classifiers and/or machine learning. The most basic algorithm is one based on human experience. The term heuristic algorithm is useful to describe a class of algorithms based on learning through discovery and incorpo- rating rules of thumb, common sense, and practical knowl- edge. This first class of algorithms essentially encodes all key evaluation steps and criteria used by operators as part of a procedure into the algorithm. The second class of algorithms is a model-based inversion that uses a “first principles” physics-based model with an iterative scheme to solve char- acterization problems. This approach requires accurate forward models and iteratively compares the simulated and measurement data, adjusting the model parameters until agreement is reached. The third class of algorithms covers statistical classifiers and machine learning, which are built through the fitting of a model function using measurement “training” data with known states. Statistical representation of data classes can be accomplished using either frequentist procedures or Bayesian classification. Machine learning and AI are general terms for the process by which computer programs can learn. Early work on machine learning built upon emulating neurons through functions as artificial neural networks using layered algorithms and a training process that mimics a network of neurons (Fukushima and Miyake 1982). In recent years, impressive advances have been made in the field of machine learning, primarily through significant developments in deep learning neural network (DLNN) algorithms (Hinton et al. 2006 LeCun et al. 2015 Lewis-Kraus 2016). Large sets of high-quality, well-characterized data have been critical for the successful training of DLNNs. As well, software tools have been devel- oped for training neural networks that better leverage advances in high-performance computing. A recent ME TECHNICAL PAPER w ia and human-machine interfaces NDT inspector/ engineer Test article NDT algorithms and models (artificial intelligence, digital twin) Human-machine interface (HMI) NDT automation control (scan plans) NDT automation hardware (scanning, cobots, drones) NDT sensors and data acquisition (SHM/IoT, databases) NDT 4.0 intelligence augmentation (IA) NDT 4.0 software NDT 4.0 hardware Figure 1. Vision for NDT 4.0: intelligence augmentation (IA) for NDT inspectors and engineers is achieved through a human-machine interface to NDT automation hardware, sensors, and data acquisition algorithms and models.

J U L Y 2 0 2 0 • M A T E R I A L S E V A L U A T I O N 871 overview on algorithms for NDT classification is summa- rized in a previous paper (Aldrin and Lindgren 2018). Benefits of Algorithms/AI in NDT There are a number of advantages associated with incorpo- rating algorithms as part of an NDT technique. First, algo- rithms are typically very good at performing laborious and repetitive tasks. For most parts under test, either in manufac- turing or in service, the presence of critical NDT indications is a fairly rare event. Therefore, the data review process can often be a tedious task for most operators, who can expect mostly good parts. Second, given the amount and complexity of some data review tasks performed for some inspections, such tasks can be a challenge, especially for inexperienced inspectors or inspections that are rarely performed. This trend appears to be growing with the increasing quantity of data acquired with automated scanning and array sensing systems. Third, in many instances, algorithms can perform the data review task faster than manual review, providing potential savings in maintenance time and costs. Fourth, algorithms are typically not biased by expectation, such as the frequency of indications in past inspections. With a reduction in errors, the overall risk of maintaining a component can be improved. Fifth, algorithms can be designed in such a way to support the operator as a “digital assistant.” Algorithms could potentially help alleviate the burden of “mostly good data” and allow operators to focus on key data review tasks. As well, algo- rithms can be used to reduce the size and dimensionality of NDT data and present the operator with a reduced feature set for manual classification. Lastly, there are challenges with the aging workforce and transitioning expert knowledge to the next generation. Algorithms, if designed properly, can be repositories for expert knowledge in an NDT organization. Challenges of Algorithms/AI in NDT While the application of NDT algorithms shows great promise, there are a number of potential disadvantages with applying algorithm-based solutions to NDT inspection problems. First, the development and validation of reliable algorithms for NDT can be expensive. Training DLNNs requires very large, well-understood data sets, which are frequently not readily available for NDT applications. While the NDT community often possesses a large amount of data, the material state behind the data is often not perfectly known. Acquiring data from parts with well-characterized damage states, such as cracks, corrosion, or impact damage, requires either high-resolution NDT techniques for finger- printing, or destructive characterization for full verification. The design, training, and validation of algorithms also require unique software development skills and many hours of engi- neering labor to successfully implement. Second, algorithms also can perform poorly for scenarios that they are not trained to interpret. There have been concerns for decades about the reliability and adaptability of machine learning algorithms to completely perform complex NDT data review tasks. In NDT, many promising demonstra- tions have been performed by the NDT research community, but frequent issues concerning overtraining and robustness to variability for practical NDT measurements outside of the laboratory have been noted (Aldrin and Lindgren 2018). Prior successful NDT applications of neural networks have been dependent on taking great care to reduce the dimension- ality of the data and provide reliable features as inputs for clas- sification. As well, designing algorithms to address truly rare events—so-called black swans—is extremely difficult (Taleb 2007). Third, while human factors are frequently cited as being sources for error in NDT applications, humans are inherently more flexible in handling unexpected scenarios and can be better at making such judgement calls. Human inspectors also have certain characteristics like common sense and moral values, which can be beneficial in choosing the most reason- able and safest option. In many cases, humans can detect when an algorithm is making an extremely poor classification due to inadequate training and correct those errors. Fourth, for many machine learning algorithms like DLNNs, it can be difficult to ascertain exactly why certain poor calls are made. These algorithms are often referred to as “black boxes,” because the complex web of mathematical operations optimized for complex data interpretation problems does not generally lend itself to reverse engineering. Approaches are being developed to sample the parameters space to ascertain the likely source for decisions (Olden and Jackson 2002), but the field of “explainable AI” (XAI) is still in its infancy (Stapleton 2017). Lastly, with the greater reliance on algorithms, there is a concern about the degradation of inspector skills over time. As well, there is a potential for certain organizations to view automated systems and algorithms as a means of reducing the number of inspectors. However, many of these disadvantages can be mitigated through the proper design of human- machine interfaces. NDT Intelligence Augmentation With recent progress and hype on the coming wave of AI, some perspective is needed to understand how exactly these algorithms will be used by humans. While the original vision for AI was to mimic human intelligence, in practice AI has been successful only for very focused tasks. While today certain algorithms can perform better than humans for certain predefined and optimized tasks, we have not achieved the early goal of independent AI. Humans not only have the capa- bility to perform millions of different tasks, many in parallel run by the unconscious mind, but they also have the where- withal to determine when it is appropriate to switch between tasks and allow the conscious mind to have awareness as needed. The real value of AI today is using it as a specific tool (Aldrin et al. 2019).

ASNT grants non-exclusive, non-transferable license of this material to . All rights reserved. © ASNT 2026. To report unauthorized use, contact: customersupport@asnt.org